A mentor nurtures our passion and gives us the space to develop our creative skills. I learned music from the pros and helped reconstruct a classic British guitar.

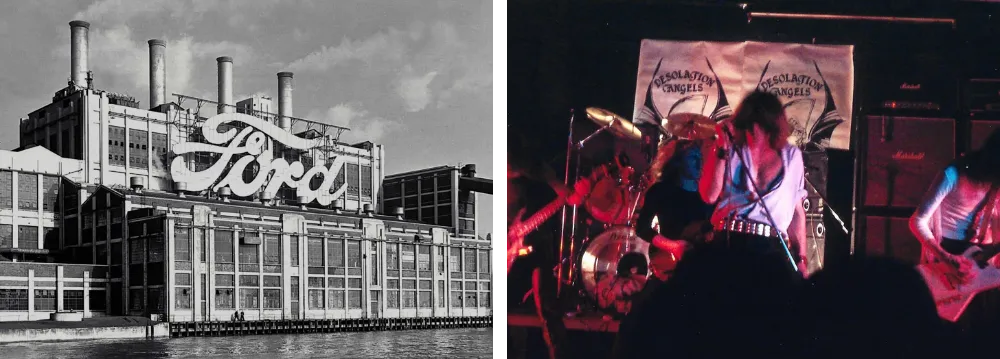

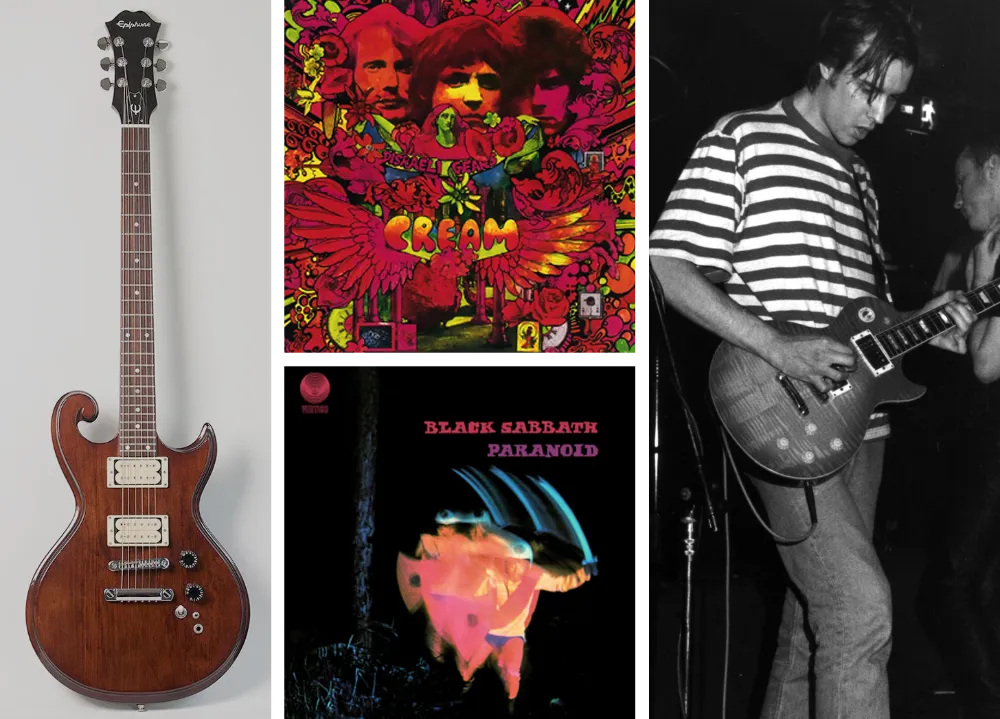

The guy who inspired me to play guitar was a friend of a neighbour. Keith lived on a council estate (the Mardyke), opposite Ford’s car factory in Dagenham, East London. This was the mid-1980s, I’d given up on school. Every week I’d catch a short bus ride down to his flat and just sit, watching Keith jam on the guitar. He was mid-30s and had gigged in his youth. I didn’t own a guitar yet, so it was frustrating, waiting for a rare opportunity to play Keith’s Epiphone Scroll. He played hard rock, as good as Black Sabbath’s Tony Iommi. Keith’s biggest hero was Eric Clapton.

Within weeks I bought my first electric guitar for £50 and we started a band together. We pinned a handwritten postcard ‘Bass Player/Drummer Wanted‘ to the noticeboard of a local music store. Answering the ad, Mark became our bass player and was closer to my age, though still ten years older at 26. Mark also had wheels and wasn’t a drinker so was always happy to drive. We’d all go to pub on Friday nights to watch other bands. This became an obsession, taking mental notes of how musicians performed, what gear they used.

Our rock band, lead by Keith on guitar, rehearsed at a studio every week, though we never played a gig. However, this experience served as valuable musical training. I learned how to perform with other musicians, how to structure songs and play in time with a drummer. Lots of drummers came and went, all with very different styles. One drummer sticks out in my mind. He looked like Ian Anderson from Jethro Tull and was not the most gifted drummer. But he had the rock star swagger.

I began imagining my own future band. We would need to look cool, as well as play well. The older guys I was jamming with were too straight. Keith, the elder statesman was quite hostile towards the younger, emerging metal bands like Metallica or Slayer. But for me at 17, this first band had been a healthy experience, a solid training ground. My own Dad was absent throughout my teenage years, so these more senior music guys were parental figures, people to look up to.

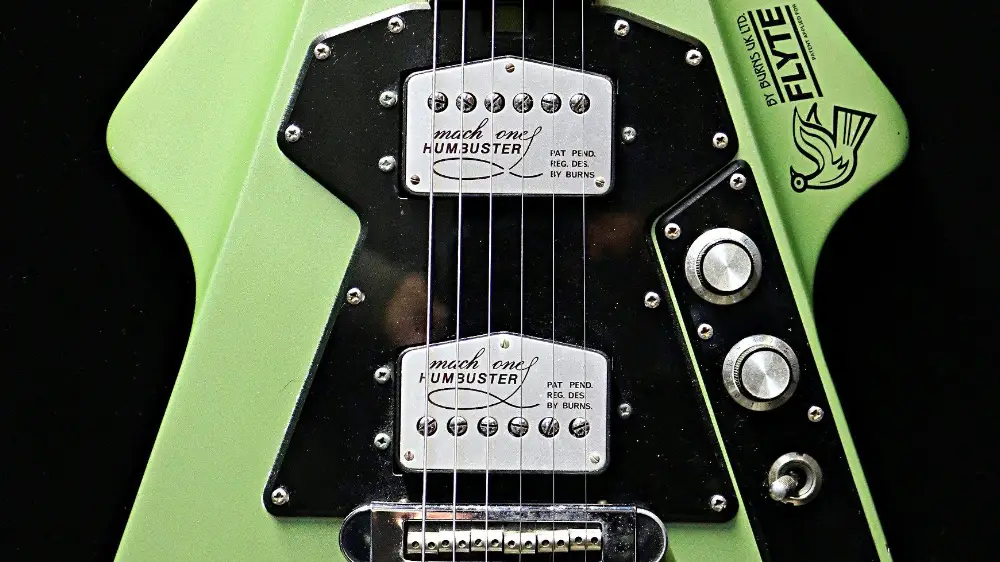

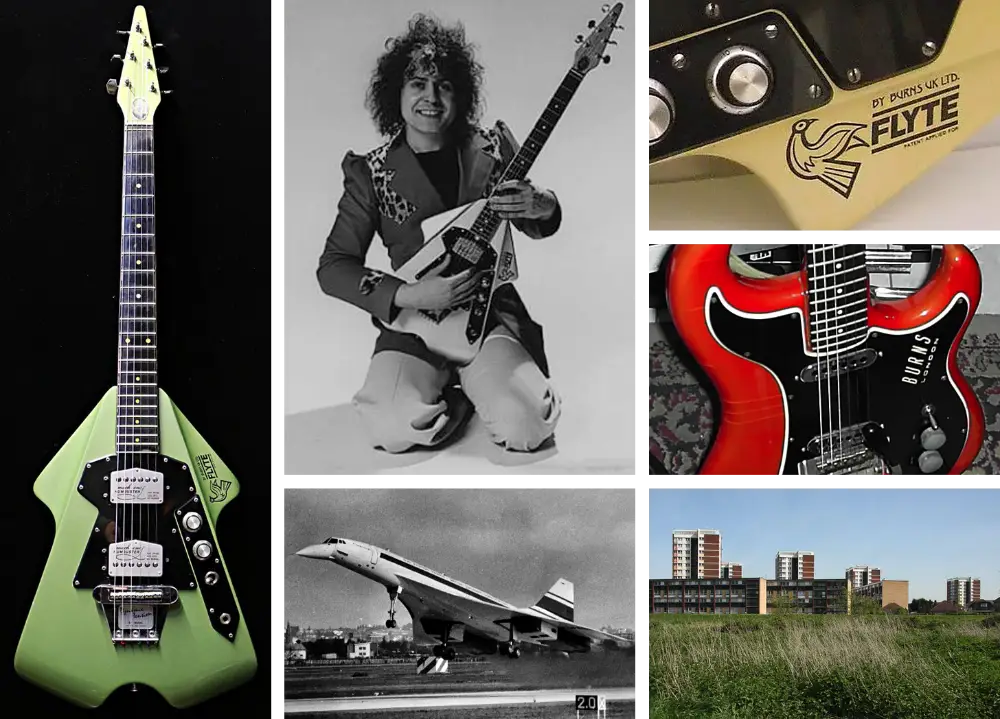

Jim Burns was, in the 1960s the most successful electric guitar maker in England. Hank Marvin (of The Shadows) had also popularised the electric guitar, inspiring legends such as Dave Gilmour and Jeff Beck to pick up the axe. So with a growing youth market for cool looking guitars, Burns spotted an opportunity. The first classic Burns models (later rejuvenated by Supergrass and Billy Bragg) were based on the Fender Stratocaster and much cheaper than a Strat. By 1970 Jim Burns guitars had reached the end of the line. However, in 1974 there was modest success with its quirky Flyte design, popular with Glam Rock stars including Marc Bolan.

The Burns Flyte shape is also similar to a Gibson Flying V but with wings. The design was inspired by the supersonic jet Concorde.

My friend and guitar mentor Keith had longed to build his own guitars. And the rocket-shaped Burns Flyte was our first project. I then helped Keith build two guitars from scratch, a 4-string bass and 6-string electric. Our first mission was to source the original Flyte body design. Obviously we weren’t going to carve the wood, with limited facilities in Keith’s council flat. After doing our research we made contact with Jack Golder (d. 1992), a former employee of Jim Burns who had set-up his own company Shergold Guitars in 1973. By the mid-1980s Jack was making furniture, but still trading in custom guitars. Me and Keith visited Jack’s Harold Wood workshop and picked up two original bare wood Flyte guitar bodies with neck, fretboards and other parts.

Back on Keith’s kitchen table we set about assembling two very unique Burns Flyte limited editions. Both guitars were to be gifts for our friend Bob, a computer engineer, lyricist and the neighbour who first put me in touch with Keith. My role in the construction of the guitars was minimal, I helped with sandpapering, spray-painting but left the trickier assembly to Keith. The finished guitars were matching colours, a deep, cyan blue with dark rosewood fingerboards and steel fittings. Neither were the best sounding guitars. This was a fun, practical project and the finished guitars looked cool. Today’s retro enthusiasts will no doubt be enthralled. And I learned the inner mechanics of a guitar, at close quarters. Keith built a few more, the same design.

Keith was a genuine guitar enthusiast in every respect. I look back and admire his dedication. He studied every part of the instrument and was a pretty handy player. The perfect teacher and someone who would shape my own playing. Though I never played as fast as Tony Iommi or Keith.

Much later we had a reunion after 20 or more years out of contact. He still lived on the same housing estate near Ford’s car factory – the Mardyke estate is where location filming took place for the 2010 movie Made In Dagenham. By this time, Keith’s small apartment was full to the brim with guitars of all shapes and sizes. He had been buying and selling guitars for a profit, as a business sideline.

We had a great evening catching up. Our mutual friend (my ex-neighbour) Bob joined us. We jammed with lots of different guitars from Keith’s large collection, including a Brian May Red Special. Keith noted my playing was pretty good by now, though I’ve never had a great deal of self-confidence.

Bob had self-published his first book. I remember him drafting it years before, when we’d sit smoking and listening to music. Bob is a fan of Douglas Adams, so this influenced his humourist writing style.

However, I was soon to leave London and move to Brighton. Privately, I knew the evening was also likely to be a farewell. Keith was famed by friends (less by neighbours) for playing the guitar very loudly. He now lived in a newly built sound-proofed apartment on the same estate. I recall first arriving at the front door that evening. I knocked a few times, then Keith finally opened the door. A blast of loud music hit me!

Sadly a couple of years later, Bob emailed me to announce that Keith had passed away. He was in his late 60s and died prematurely. Keith had suffered a severe brain tumour at home. The last time we spoke Keith had talked about his session guitar work with a Country singer. I felt really pleased that he finally had got some recognition for his lifetime’s dedication to music and in particular, the guitar.

To outsiders Keith would appear eccentric and carefree, which is what I admired. The benefits of being intensely focused and fearless without distraction, is that it matters less how others judge you. Like any truly dedicated artist, Keith funded his passion by taking factory jobs, so he could pour his creative intellect into the music.

I am greatly fond of this period of my life, by Keith’s relentless dedication to music. I also got to meet craftsman Jack Golder, co-founder of the Shergold guitar brand and help reconstruct a classic British instrument.

Explore further on Burns and Dagenham:

- Watch the Burns Flyte in action from the Guitar Collection channel.

- Made In Dagenham is a wonderful movie, telling the story of women Ford workers fighting for equal pay back in the 1960s.

- Burns guitars are still coveted by style-conscious musicians and are highly valued on the secondhand market.

- The present Shergold Guitars website (now owned by Barnes & Mullins Ltd), a guitar brand co-founded in 1967 by Burns employee Jack Golder.